Unlearning: Brain Science, UDL, and Practical Steps to Change Your Mindset and Classroom

Habits can be a good thing. These mental shortcuts save us time and energy.

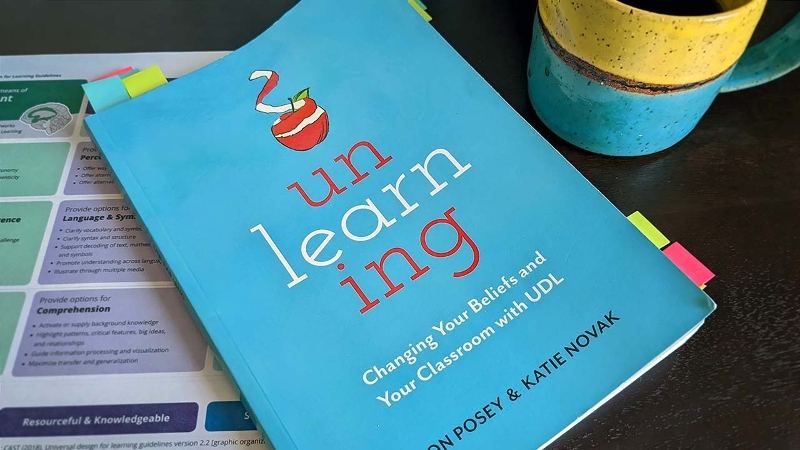

“We go for a walk, take out our notebooks when we get to a class, or whatever the routine action may be,” note co-authors Allison Posey and Katie Novak in Unlearning: Changing Your Beliefs and Your Classroom with UDL.

“We don’t have to think about how we brush our teeth because we have been doing it for so many years in roughly the same way — and this is a good thing in terms of our cognitive capacity,” they write.

Most of us only have so much mental bandwidth, and anything that helps us manage our routines can be helpful.

But habitual behavior and thinking can also be an Achilles heel when trying to make substantive changes — like, say, incorporate Universal Design for Learning in the classroom. That’s where “Unlearning” swoops in.

“Unlearning” Shows Teachers How to Become Expert Learners

Andratesha Fritzgerald, author of Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success

UDL expert Andratesha Fritzgerald describes Unlearning as a “small, but mighty, very accessible” book. Fritzgerald knows something about the heavy lifting required for meaningful change, as the author of Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success and founder of Building Blocks of Brilliance, a consulting company that helps teachers and leaders create more equitable learning environments.

As it relates to her work in equity and antiracism, Fritzgerald brings a deep understanding of the variability of learning and what’s required to transform tried and true techniques. When thinking about breaking old habits and routines to try new tools, Fritzgerald says teachers must go from being the expert in the room to being the expert learner alongside their students, and embrace any uncomfortableness that comes with that shift.

“To meet the needs of students, who are all different, means I’m going to have to learn some new things, too, and in learning new things, this gives me a chance to model what Universal Design for Learning calls an expert,” she explains. “I get to be the expert learner, and my students, my learners, and my colleagues get to teach me.”

COVID Pandemic Forces Us Out of Our Habit Comfort Zone

Published by CAST in February 2020, the book “Unlearning” arrived just a few weeks before the pandemic threw all kinds of routines into upheaval and demanded dramatic change.

Allison Posey, co-author of Unlearning: Changing Your Beliefs and Your Classroom with UDL

“All of a sudden, we all were having to unlearn so many of our habits and routines in order to stay safe,” says Posey, who is also CAST’s Senior Content Editor and Producer.

The public health crisis laid bare the uneven access students had to things like the internet, and revealed widespread problems with student disengagement. The shifts in education related to the early response to COVID-19, including teachers, students, and parents needing to quickly transition in many cases to virtual e-learning, brought these disparities into sharp focus.

“What we started to understand over time is that practice doesn't just change, we actually have to unlearn a lot of our habits and routines in order to change,” Posey says in a video promoting the book.

But the need for a book far predates the pandemic. And the fact that an idea like UDL can be embraced, but not put into practice for a very long time isn’t new, either.

The authors point to a hundreds-year-old story of the scurvy cure that was largely ignored for years, even though it saved lives, as evidence of how difficult unlearning old practices and implementing new ones can be. The authors cite social scientist Everett Rogers’ 1962 classic, Diffusion of Innovations, as the source of this story.

As Rogers tells it, in the 1400s, when seafaring was common, Captain Lancaster lost many men to what was then a mystery illness. describes how Lancaster happened upon a powerful prevention for the condition. He doesn’t say how Lancaster came to this discovery, but all the same, Rogers notes in his case study how Lancaster set out to test it.

“Lancaster had four ships headed out for exploration, so he took the opportunity to select one group for treatment,” write Posey and Novak. “The men on that ship were lucky enough to ingest three teaspoons of lemon juice each day to ward off the illness. Every one of the crew survived the journey.” Sailors on the other ships, however, were not so lucky, and more than half died.

Naturally, you’d think other captains would use the same approach as Lancaster, and immediately adopt this new, lifesaving routine. In some limited instances, Lancaster’s findings were replicated. But, as noted in the playfully named opening to Unlearning, “Three Teaspoons of Lemon Juice: Not an Introduction Because Not Everyone Reads Those,” it wasn’t until centuries later, around the late 18th century, that the British Navy endorsed the treatment.

In short, change can take a painfully long time to be realized, and Novak and Posey hope to expedite adoption of UDL by writing this book.

“We want to see this change for our kids,” Posey says. “We want this to change for every student right now in every school system.”

Teacher Follows “Unlearning” Cycle to Implement UDL

This sort of roadmap thinking — deciding not only what needs to happen, but how we get there — compelled Mark Thompson, high school social studies teacher and an instructional coach at Sheboygan Falls School District in Wisconsin, to find out more about “Unlearning.”

The book lays out the Unlearning Cycle, five steps (though they needn’t necessarily occur in a particular order) to help educators implement UDL:

- Understand variability

- Know your goals

- Transform tried-and-true techniques

- Prioritize engagement

- Scaffold expert learning

It expounds on each, and is written in a way that practices what it preaches, from acknowledging individual differences in teaching to learning how to provide the compelling brain science behind our unchanging ways, and how to overcome them.

“I like the structure of it. …I like the fact that they broke it down into those steps, into that cycle,” Thompson says. “Most teachers, when you explain the concept [of UDL] — they will agree with it.”

But, he adds, “There’s always this kind of mental block when it comes to, ‘Well, how do I get there? How do I go from believing that students are variable — that they’re all different — to the point I can design learning to help them?’”

Although, the publication of Unlearning certainly wasn’t planned to coincide with the outset of a pandemic — with its lessons applied well before, and outside that context — the timing has certainly piqued interest.

David Gordon, CAST Chief Content Officer

“Unlearning was exactly what people needed as schools, teachers, students, and parents quickly pivoted and made rapid adjustments in the classroom and at home,” says David Gordon, CAST’s Chief Content Officer and the book’s publisher. “No surprise, then, that the book has been a bestseller for us. It’s really about improving your practice, improving yourself, and continuing to grow as a learner and as an educator.”

Gordon adds in addition to continuing strong sales in English-speaking world, the book will also appear in other languages around the world. Korean publisher Hakjisa is the first to purchase translation rights.

Apples are Red, Even in the Dark

To grow as a learner and educator, it helps not only to have a plan, but to understand what’s going on in the brain when following a routine or creating a new one.

For instance, why do assumptions have the power to undercut the best intentions, and how can lived experiences not only inform what you know but be an obstacle to seeing things in a new way?

Unlearning draws on the example of an apple’s redness, and the brain science behind why it’s viewed as holding that hue, even when it can’t be seen. First, as it notes, the reflections of wavelengths of light to photoreceptors in the eyes are what leads to that perception of redness.

“Neurologically, when we look at an apple, photons of light reflect off it, stimulate cone photoreceptors of our eyes, and the resultant signal is sent through the optic nerve to the multiple brain networks, including the occipital lobe of the brain,” the authors say in Unlearning. “Here, color- and shape-sensitive networks perceive the redness and roundness of the apple, and memory centers in the temporal lobes recall that this object is called ‘apple.’”

But it doesn’t stop there. Research finds people still claim to see the apple’s red coloring when it’s pitch black. In short, when there is no light to give the fruit its characteristic redness, many people will still believe they see that color, as the book points out. So what are the implications of that for the brain and classroom?

“New learning and change can be really difficult. They take energy and deliberate effort, requiring that we build new models of understanding and change what we perceive and how we act,” Novak and Posey write. “New learning requires persistence, a willingness to trade old explanations for new ones and to try new things — to get out of our comfort zone.”

That’s why unlearning has become such an important conceptual framework for making changes in the classroom.

“I prefer doing my UDL trainings now through the lens of unlearning,” Posey says, because it helps teachers to see that change takes time, it’s difficult, and it’s not just about implementing guidelines.

“It’s about thinking about your equitable practices,” Posey explains. “How are your practices actually inclusive? Do they include all students? And where they’re not, you now have a process to go through to think about changing those practices. So, I hope it helps contextualize UDL a little bit more.”

Adopting UDL Requires a Change in Mindset

Adopting UDL isn’t a rote additive exercise, like incorporating new practices in the classroom with an existing approach, as much as it’s about changing a mindset.

Katie Novak, co-author of Unlearning: Changing Your Beliefs and Your Classroom with UDL

“It’s not like you’re trying to make extra room, as much as you’re throwing something out so there is room,” explains Katie Novak, the author of 10 books on UDL implementation and the CEO of Novak Education. “That’s painful because there’s like this grief of letting go, and then there’s also a hit to your ego.”

You’ve been doing something a certain way for a long time, and now you’re changing that. There’s a social-emotional impact of letting go of these beliefs that you used to align to, she adds.

With UDL, it’s not just about providing choices to learners, but making a more significant mindset shift. “Let’s really challenge our beliefs about student labels and about traditional leveling,” Novak adds. “Let’s talk about what variability really means and why it’s not an effective practice to put students in ability groups based on some preconceived notion of what success is. Let’s really talk about what variability means, and then let’s think about, based on that variability, how does our instruction create barriers for learning?”

The book provides the Unlearning Cycle to help educators change practice and remove those barriers. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy or provides a simple cookbook recipe approach. “Everybody wants a really quick solution, and this is not a quick solution,” Novak emphasizes.

Of course, that doesn’t mean change isn’t possible either. It’s just, as the Unlearning focus makes clear, it takes changing one’s beliefs to get there. “We don’t improve teaching just by building a skillset,” Novak says. “We also improve our own teaching by challenging our own mindsets.”

Story by Red Pen Content Creation.

Grab your copy of Unlearning today

CAST Professional Publishing produces books that help educators at all levels improve their practice—and change students’ lives—through Universal Design for Learning. We create, nurture, and distribute exceptional media products that inspire and inform educational research, instructional practice, and policy making for the betterment of all.