“Test scores show historic COVID setbacks for kids across U.S.”

“U.S. math, reading test scores plunge for students across the country…”

“California test scores show deep pandemic drops; math worst”

Recent headlines certainly paint a dire picture of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on learning loss for America’s children. In California’s Far North region, where students attend schools in rural and remote areas with little resources, the level of learning loss rose even higher due to the trauma caused by devastating wildfires compounded with the pandemic.

In an area where low-income students already faced a multitude of other challenges to learning, raging wildfires decimated communities, claimed lives, burned down a school and an historic bridge, and even leveled an entire town — all within the past five years.

“The people of the Far Northern region have had to live through these horrors, and the aftermath,” says Minden King, a longtime educator in Butte County, situated in the northern part of the state directly between the Plumas and Mendocino national forests. “Our towns, county offices, school districts, and communities have had to literally rise from the ashes.

“Combined with a global pandemic that left many of our students in remote areas without rigorous schooling, little or no teacher contact, and without access to much needed intensive supports, the already prevalent achievement gap for low-income students only grew and intensified,” she says.

To help students, families, and educators navigate through these multi-layered traumas and find their way back to real learning, King applied for and received funds for a 3-year Comprehensive Literacy State Development Grant in June 2021 from the California Department of Education.

Her grant, named “The Far North Literacy Development Consortium (FNLDC),” spans four counties, including Butte, Plumas, Shasta, and Modoc — all areas with high numbers of socioeconomically disadvantaged students, who consistently perform academically lower than the state average. At the core of the grant is the need to focus on building teacher capacity through robust professional development and coaching, then training other educators to carry on the work with other school districts.

“Our focus is really healing that layered trauma through literacy,” says King, who serves as the FNLDC Grant Director, in addition to her role with the Butte County Office of Education. “The ultimate goal is to make this pilot school project a model for other schools and districts to replicate.”

To do so, the FNLDC partnered with CAST, the creator of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a framework used to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all based on scientific insights into how humans learn. Now in its second year, the FNLDC project is gaining momentum and starting to show results.

Read on for a glimpse inside this pilot project, and learn about its potential impact as an inclusive literacy instruction model for the entire state.

What is the Far North Literacy Development Consortium?

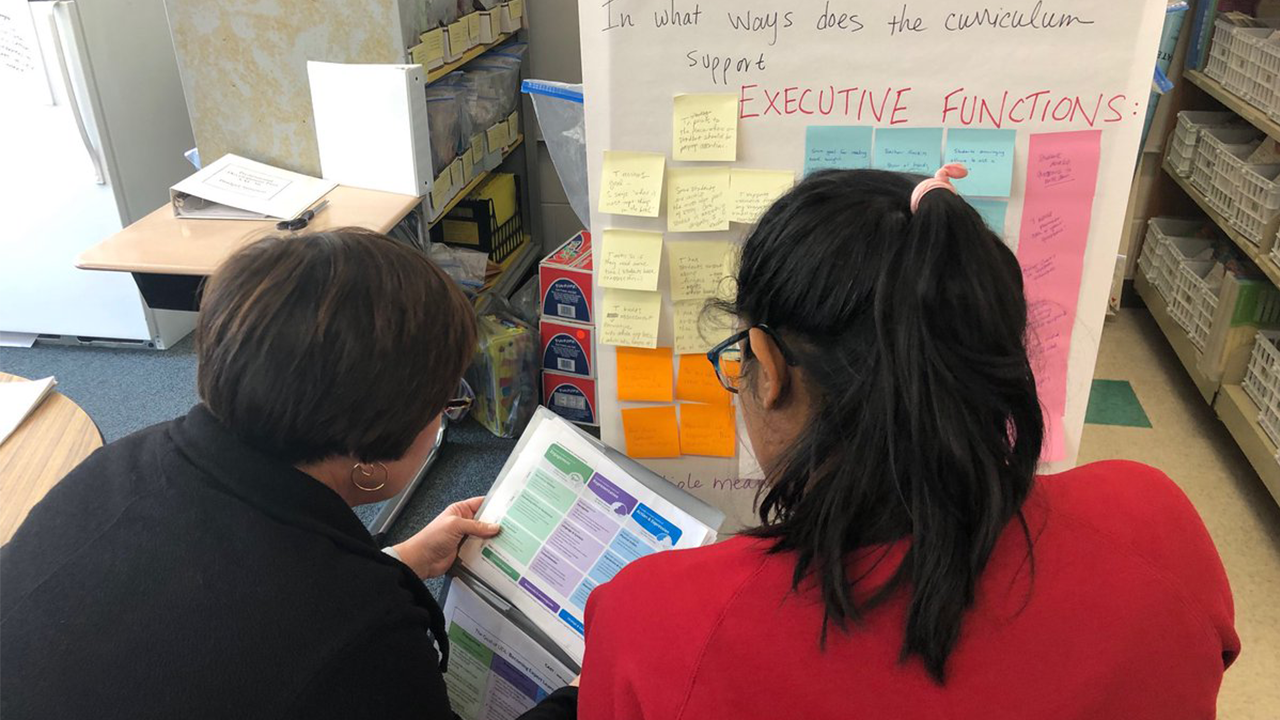

The FNLDC project includes about 70 teachers, county office administrators, literacy coaches, and principals in the Far North counties of Butte, Plumas, Shasta, and Modoc counties. The project focuses on improving literacy outcomes for students in grades six through 12 from seven schools in four school districts. The FNLDC educators partner with the CAST team to learn about the Universal Design for Learning framework, how to apply UDL to improve literacy instruction across all disciplines, then train others by creating peer-to-peer coaching models.

“They really have the motivation and determination to rebuild their commitment to students and return to learning in the face of all the tragedies they’ve experienced in the last few years,” CAST Implementation Specialist Dr. Sylvia Rodriguez Douglass says of the FNLDC. “They saw Universal Design for Learning as this powerful tool to reach learners that, historically in this area, have not been very successful.”

Essentially, the FNLDC will utilize UDL strategies, guidelines, and practices to help teachers design lessons, choose materials, and improve instructional practice in a way that intentionally mitigates or removes barriers to meet the needs of all learners. Teachers will empower students by valuing their voice and choice, which in turn improves engagement. A focus on family literacy will help the community understand the importance of developing literacy skills, which students need for every subject, including math, science, English, and others.

Improving Academic Achievement for Schools in Need

The particular schools involved in the FNLDC project were selected based on their percentage of low-income students as well as their poor performance on statewide academic achievement tests, such as the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) for English language arts (ELA)/literacy and mathematics.

In the Far North region, socioeconomically disadvantaged students make up the largest student group, with an average of 64% of students eligible for free and reduced meals, which is approximately 6% higher than the statewide average. King included the following representative graphic in her literacy grant application to the CDE:

| Category | % Socioeconomically Disadvantaged | 6th Grade 2019 ELA CAASPP % Met or Exceeded | 7th Grade 2019 ELA CAASPP % Met or Exceeded | 8th Grade 2019 ELA CAASPP % Met or Exceeded | 11th Grade 2019 ELA CAASPP % Met or Exceeded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statewide Average | 60.7% | 50.01% | 51.37% | 49.41% | 57.27% |

| Butte County: Biggs Unified School District | 66.3% | 38.1% | 35.29% | 10.00% | 42.5% |

| Shasta: Happy Valley | 63.7% | 35.0% | 54.28% | 27.27% | N/A |

| Plumas: Plumas Unified School District | 72.7% | 28.91% | 36.99% | 39.65% | 50.0% |

Percentage of Socioeconomically Disadvantaged and ELA CAASPP Inequities

“Poverty compounded with substantial trauma due to wildfire devastation and loss of loved ones, combined with isolation and depression caused by school closures, have resulted in creating monumental barriers to academic achievement,” King wrote a year ago, as she described the dire learning situation for many students in the Far North.

Fast-forward to October 2022, and the Nation’s Report Card — the most extensive measure so far of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on student achievement — shows drops in math and reading scores across the country. In California, specifically, students meeting state math standards plummeted 7 percentage points to 33%, and the percentage meeting English language standards dropped 4 percentage points, to 47%, according to the report.

In an October presentation to the CDE, Butte County Literacy Coach Nick Wilson explained why the FNLDC is focusing on trying to improve literacy instruction across all disciplines.

“When you factor in our region’s Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) rates – among the highest in the state – generational poverty, and an uncertain economy on top of COVID-19, we arrive at the endemic barrier to learning – layered trauma,” Wilson says. “Trauma is the primary barrier to learning that UDL helps us to navigate.

“As part of this grant, it’s imperative to observe that cultivating literacy isn’t just the intended outcome, it’s the very means by which we can navigate our collective trauma, and in doing so, work through that obstacle toward engagement,” he adds.

Learning How to Apply UDL in the Classroom

Sixth-grade teacher Cindy Thackeray says understanding the concept of UDL definitely piqued her interest, but it also intimidated her at first.

“I was really enamored with the concept, but overwhelmed by the implementation,” says Thackeray, a Plumas Charter School educator participating in the FNLDC project.

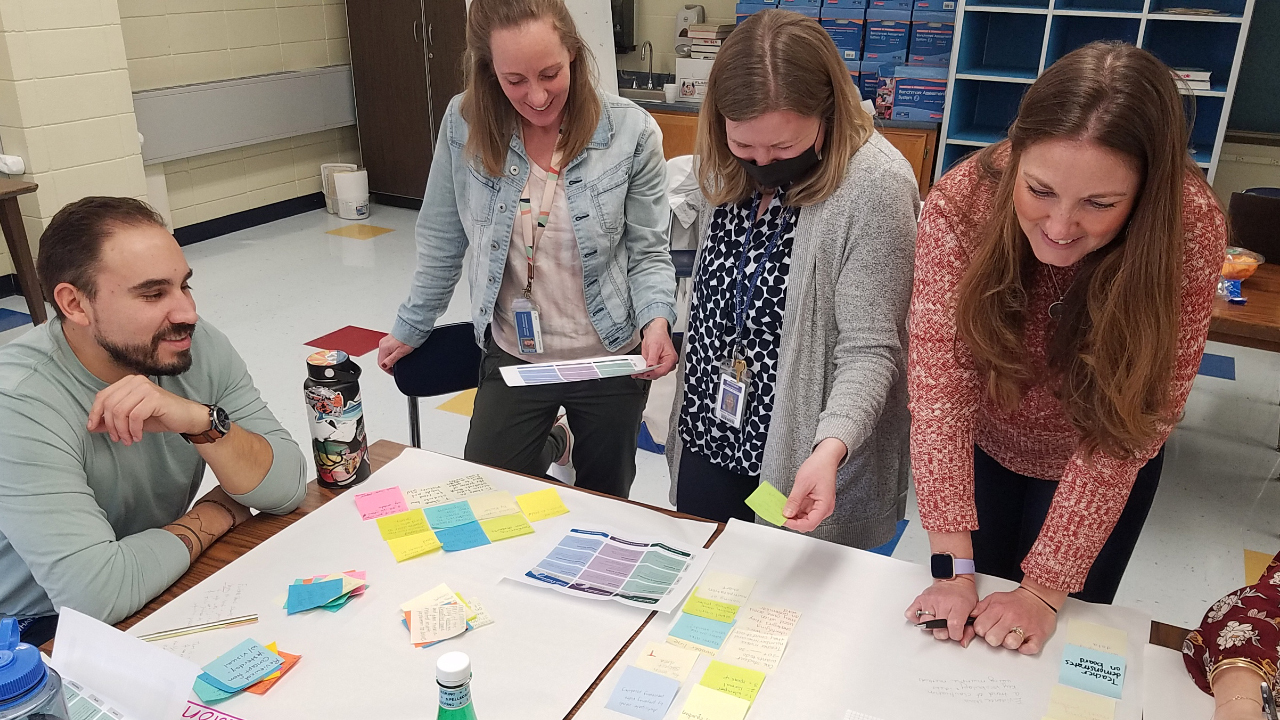

With COVID in full swing at the start of the project in Fall 2020, the FNLDC kickoff event pivoted to a virtual platform, followed by monthly virtual professional development sessions led by CAST. In the first year, educators dove into the “why” of the Universal Design for Learning framework. This year, the team will focus on how to apply UDL practices with in-person coaching and professional development sessions.

“I feel like CAST did an amazing job with helping us to not be overwhelmed with the concept, trying to find little ways where we can create more opportunities, choices, and options for students, as well as engaging them in the process,” Thackeray says.

For instance, Thackeray discovered how making a small tweak to the layout of her classroom and offering flexible seating options for students could dramatically boost engagement.

“I’m really letting the kids choose: ‘Do you want to work independently? Do you want to sit with this group?’ And then letting them move around the classroom. I got some floor chairs. I have some sitting desks that also change into standing desks,” Thackeray says. “It was amazing. Just changing those boundaries for them. That in itself, I felt, was a big deal for the kids. Just having that choice allowed them to be more engaged.”

Throughout the pandemic and natural disasters, Thackeray learned the importance of creating a safe learning environment for students.

“UDL is really helpful in terms of giving me permission to try to set my designs, scaffolding, or options to meet a student where they currently are. Individualizing, looking at them where they’re at, then trying to figure out a way to meet their needs,” she says. “I also learned that my job is not to just teach them information, but to help create expert learners.”

Ultimately, Thackeray says learning UDL concepts and best practices in the classroom changed her mindset and it’s helping her be a better teacher.

“The most powerful change is I’m enjoying my job more,” Thackeray says. “I love the challenge of trying to do something different. I love the permission to individualize and look at each kid, then try to teach that. I feel like I have been given this great opportunity to not just teach math and reading, but create expert learners. And for me, that reframing of my position has been a huge difference maker.

“It’s not just about literacy,” she adds. “Once you help them to become expert learners and keep them engaged, that’s going to translate across the board into all subject areas of their life. We need to remember, the kids aren’t broken. The system is.”

Fixing the System, Step by Step, with Focus on UDL

Representing small school districts in the Far North with limited resources and funding available, King says educators participating in the FNLDC project feel very appreciative to be receiving quality professional development instruction from a world-renowned organization like CAST.

“It’s been a great experience for us,” King says. “CAST has been wonderfully responsive to our local context. I feel like we’ve really taken off and things are happening.”

While the first year got off to a slightly rocky start due to COVID learning disruptions, the second year kicked off with an in-person back-to-school event focusing on family community outreach.

“We coordinated with our local library and they brought a 36-foot bookmobile bus to our back-to-school night at our pilot school and, boy, that was a hit!” King says. “The kids loved it, the parents loved it, and it was awesome.

“Through this partnership, we were able to connect families with resources, library cards, and audio books,” King adds. “We also provided every child in the school with a swag bag that included two books, as well as literature to guide parents in facilitating intentional and meaningful reading at home.”

Conducting hands-on and face-to-face meetings with families this year truly made a difference, King says.

“Being able to get culturally responsive books into our classrooms and libraries of our pilot schools has enabled students to see themselves in print, which helps build the bridge necessary to promote healing,” King adds. “This has been incredibly rewarding for us all.”

Once educators learn how to apply UDL to literacy instruction this year, the focus in Year 3 will be about positioning these educators as solid UDL trainers to teach others across the state, using this pilot project as a best-practices model.

Dr. Rodriguez Douglass, the CAST Implementation Specialist, says even after the grant expires, the county office of education leads, administrators, and coaches will continue the UDL work to help other school districts improve their literacy outcomes.

“These 3-year contracts really are about training the trainer and leaving folks in the position to continue on this work,” Dr. Rodriguez Douglass says. “They’re going to be equipped enough after these first two years that they can start training other people at their sites.”

Interested in bringing UDL to your state?

CAST partners with states, districts, and schools to build understanding, design strategies, and support the implementation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), accessibility and inclusion, professional development, and more.

CCIL: Inclusive Literacy for California Students

We’re working with California educators to design and deliver more inclusive literacy instruction.

IEP Improvement Project: Empowering Massachusetts Schools to Improve Service to Students

Family engagement in the IEP process is essential. Learn more about our professional learning work in Massachusetts to ensure a more equitable IEP process.

NH UDL: New Hampshire UDL Innovation Network

We’re supporting New Hampshire educators in building and sustaining a state-wide model for UDL implementation.